49: A door back into paradise

The lie that’s told to us over and over again that without oppression we are monsters

Monograph of the Paradiseidae, or birds of paradise and Ptilonorhynchidae, or bower-birds.London :H. Sotheran & Co.,1891-98.

CW: There’s a brief reference to sexual violence in this one.

When we talk about writers exhibiting prescience in their work, I think it actually undervalues what it is that they are doing as a kind of lucky guess or knack for predicting. I say undervaluing, because what actually seems to be happening here is that these people are exhibiting an understanding of certain core natures of humanity or the world—deep truths that exist outside of time and dependably resurface.

I was feeling a lot of these truths some of which were preeeetty sucky back in early 2017 when I first read Rebecca Solnit’s 2004 book Hope in the Dark, which comments largely on the Iraq war and the Bush era, but post-2016 election felt like she was writing directly to me, right when I was reading it, about our current political hell and where to find hope. And I had a very similar experience recently reading Solnit’s 2010 book A Paradise Built in Hell, which is about human nature during disaster.

I’m a pretty big fan of Rebecca Solnit for a lot of reasons, one of which is the way she uses form and genre. She combines elements of straight journalism, commentary, and lyrical personal essay into this layered version of creative nonfiction that feels modern and sometimes bloggy but also kind of timeless. I also find Solnit’s prose challenging in a really good way, in that she punctuates her just-the-facts retellings with these beautifully crafted sentences that are full of meaning and reward revisiting.

Anyway I talked a little bit about the book in a past issue, but we’re back for another episode of the Solnit Corner today to get into its core themes, specifically the false narrative of human savagery, and the way catastrophe is compounded by panic among elites.

The book is basically a history of human response to disaster and the field of disaster studies within sociology. The core argument challenges the Hobbesian belief that humanity by nature is violent and self-serving, and that disasters peel away the thin veneer of civilization and send us into a state of chaos and violence. In reality, Solnit and scholars cited in the book point to abundant evidence that “there are plural and contingent natures—but the prevalent human nature in disaster is resilient, resourceful, generous, empathic, and brave.”

More often than not, disaster leads us to call upon our best selves and form these impromptu utopias of collective caretaking and cashless mutual aid. In addition, what we believe about humanity—whether we consider it good and valuable or harmful and disposable—creates a self-fulfilling prophecy in how we behave toward each other during difficult times:

Katrina was an extreme version of what goes on in many disasters, wherein how you behave depends on whether you think your neighbors or fellow citizens are a greater threat than the havoc wrought by a disaster or a greater good than the property in houses and stores around you.

Solnit catalogues many catastrophes throughout history, which in itself is pretty fascinating (I knew nothing about the Halifax explosion of 1917), along with overlooked stories of neighbor-to-neighbor relief efforts in which people go above and beyond to help each other and experience moments of joy in doing so.

So that’s the running theme, but there are lots of eye-opening subtleties within it, largely around what is actually behind the violent conflict that does sometimes follow disaster. Solnit doesn’t claim that there is no bad behavior during disaster, merely that the fear of mass panic or a reversion to savagery is far overblown. Meanwhile, some of the worst violent offenses during catastrophe are carried out by the state, terrified of losing control, or by private property owners who turn on their neighbors out of fear of losing their possessions. She explores the idea of “elite panic” that emerges among the ruling classes:

Elites and authorities often fear the changes of disaster or anticipate that the change means chaos and destruction, or at least the undermining of the foundations of their power. So a power struggle often takes place in disaster—and real political and social change can result, from that struggle or from the new sense of self and society that emerges. Too, the elite often believe that if they themselves are not in control, the situation is out of control, and in their fear take repressive measures that become secondary disasters.

Elite panic usually emerges in fear of, above all else, property crime, even in situations where human life is at stake and commerce has become largely halted. Her retelling of police and federal troops shooting on sight or brutally arresting San Franciscans thought to be stealing from stores in the aftermath of the 1906 earthquake ring true in 2020.

I also like the way Solnit describes the good we do for each other, and the sharing or dissolving of ownership that happens in the face of disaster, not as an abnormality, but as a default setting that we fall back into when structures collapse. This brings to mind all of the cruel societal norms that many communities handily dissolved when the pandemic first took hold.

But the real centerpiece of the book, its most harrowing and thought-provoking section, is the revisiting of the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. While Solnit does recount the amazing acts of heroism and neighborly care that happened during the flooding, there’s also a dark story of how power structures responded to a mostly Black community in peril. “New Orleans was not just a catastrophe. It was a prison.”

It would have been bad enough if the Bush administration’s FEMA merely neglected the city, but national guard, local police, and hired mercenaries patrolled the streets treating victims as perpetrators. Authorities and the media helped stoke false rumors of violent chaos, including uncontrollable gang violence and rape of children and babies—stories that later were all but entirely debunked and retracted. Reports of homicidal rampage inside the Superdome eventually dwindled to a very small number of deaths, mostly from natural causes. But the message was already sent—this is what happens without law and order.

Meanwhile, fear and disdain toward Black families led to horrific mistreatment from both law enforcement and civilians. At one point, many could have walked right out of the city, across the river to the nearby suburb of Gretna, but the sheriff and a group of unidentified men with guns closed the bridge to pedestrians. “They responded that the West Bank was not going to become New Orleans,” one person recalls. Solnit refers to an earlier section on the aftermath of September 11, when thousands of New Yorkers peacefully fled on foot across the Brooklyn Bridge. She quotes Rev. Lennox Yearwood: “What if they had been met by six or eight police cars blocking the bridge, and cops fired warning shots to turn them back?”

Solnit also recounts a story that, working with The Nation and investigative reporter A.C. Thompson, she was able to break in 2008 after being turned away by mainstream news outlets. In the aftermath of Katrina, it was common knowledge that groups of white vigilantes were indiscriminately killing Black people under the banner of protecting private property. The reporting focused on the neighborhood of Algiers Point, a mostly white community that was largely spared by the hurricane. A group of white men in the neighborhood created an informal militia to seal off the area from people outside trying to find refuge there. Later they would speak without fear of consequence about committing multiple murders. One older man boasted, on video, “I never thought eleven months ago I’d be walking down the streets of New Orleans with two .38s and a shotgun over my shoulder. It was great. It was like pheasant season in South Dakota. If it moved, you shot it.”

Solnit’s tone is usually measured and empathetic, but here her rage is palpable, at the men, but also at authorities and journalists who ignored their actions, favoring horror stories of gangs in the Superdome. Katrina, she writes, did bring out the better nature of many people, but New Orleans was also robbed of the ability to find paradise in hell.

The most optimistic of all disaster scholars, Charles Fritz, had ascribed his positive disaster experiences only to those who are “permitted to interact freely and to make an unimpeded social adjustment.” This was hardly what happened in the first days and weeks of Katrina, when many felt abandoned, criminalized, imprisoned, cast out, and then like recipients of charity—or hate.

As I was finishing this book, I was also reading about dozens of cases of people driving cars into anti-racist protestors, and gangs of mostly white vigilantes in Philadelphia, referred to as the “bat boys” because they show up brandishing baseball bats, pipes, and golf clubs. They shout racial slurs at people and have been involved in several beatings, including breaking the nose of a public radio producer, all while describing their goal as protecting the neighborhood and local businesses from looting. Similar groups have surfaced elsewhere.

I really don’t want to focus too much or close with the story of these awful men but god it just feels gut-wrenchingly relevant right now and such a familiar story. Brownshirts, pinkertons, militias. In the 1990s, Octavia Butler wrote in her novels about “Jarret’s Crusaders,” acting on behalf of a fictional president whose slogan is “make America great again.”

Despite nominally being about paradise, Solnit’s book does not paint a rosy picture. The disasters she catalogs are horrible, and some people do horrible things in their aftermath. But the point she returns to repeatedly is that cruelty is not inevitable, nor is it the predominant response. The groups of marauding men are not who we are by default, and when they do emerge, they often look very different than common fears would suggest. Often they carry badges. Or golf clubs. And they are a product of a false belief about humanity—belief in a lie that’s told to us over and over again, that without oppression we are monsters.

Links

That biotech conference in Boston led to potentially 20,000 cases of coronavirus, according to genetic tracking, even reaching into local homeless shelters. A single wedding in Maine led to the state’s largest outbreak. And that is why we call it public health and not private health.

Donald Trump has carried out an unrelenting assault on public lands, emissions reductions, and environmental protections since taking office. “He has done more to roll back and weaken environmental laws and regulations than any president in history.”

Speaking of Trump, he also had some choice words for veterans, calling them “losers” and “suckers” and of John McCain, “Guy was a fucking loser.” “[Trump] can’t fathom the idea of doing something for someone other than himself.”

Speaking of all that who is voting this November I sure as fuck am. And past elections show that voting by mail doesn’t give either party an edge. But Trump constantly shit-talking voting by mail could depress the Republican vote in this election hey whatever it takes right.

Ed Markey beat a Kennedy in Massachusetts, thank god, suggesting both a rejection of dynasty politics and the power of the climate movement.

By fighting for African accents in Black Panther, instead of British accents as the studio wanted, Chadwick Boseman was fighting against the legacy of colonialism.

The oil and gas industry is flailing, with plunging prices and a glut of product. The latest plan? Flood Africa with plastic.

Everyone thought these cool singing dogs were extinct in the wild, but then they found a bunch in New Guinea.

Rob Delaney talks about his vasectomy, and why it was the least he could do (not for the squeamish and possibly nsfw).

Comics

Before the pandemic, I picked up a bunch of old Jack Kirby anthologies at the library. I will defensively point out that I’m not really the kind of comics fan who sits around reading old superhero comics. And I really hate the Kevin Smith character version of comic book fans. I have no undying devotion to Stan Lee or his stupid cameos RIP. I don’t care who would win in imaginary fights. But boy do I love looking at Jack Kirby drawings.

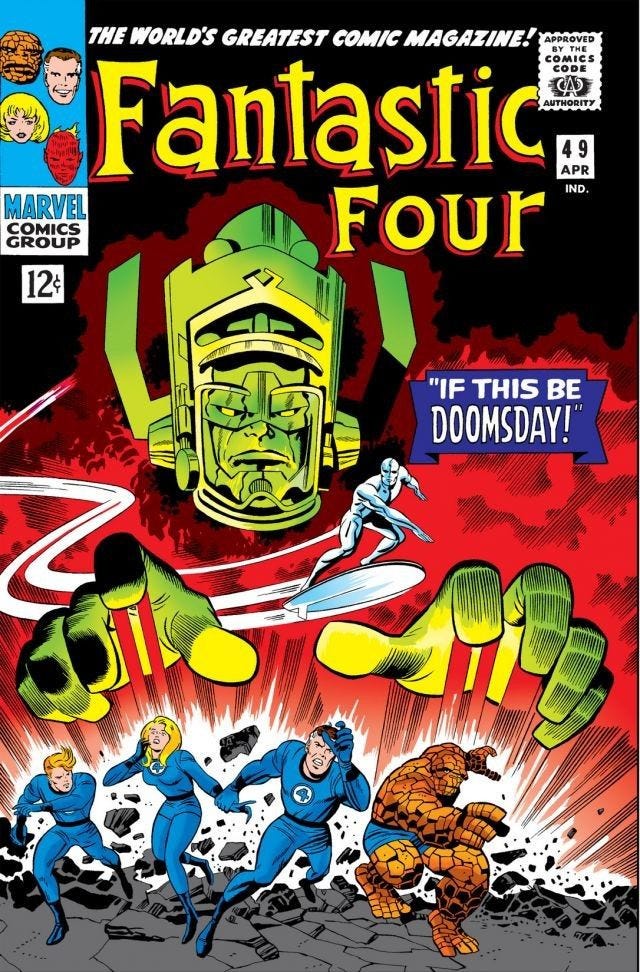

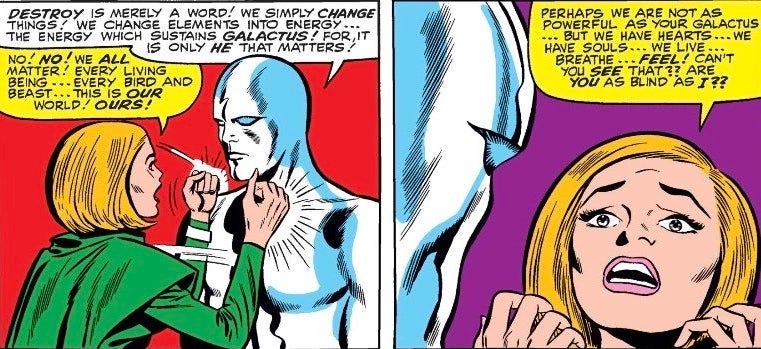

One anthology I’m reading now is of his oldest work for Marvel. The first half or so was kind of underwhelming, some early capes stuff, war comics, westerns. But then comes Fantastic Four 48, 49, and 50 from 1966 and oh my god. Only the second work in the book featuring Kirby’s pencils with Joe Sinnott’s inks and there is something about the combination of those two and the subject matter, which is the introduction of Silver Surfer and Galactus.

Something happened to Kirby’s style where he doubled down on these super heavy black outlines and overly dramatic facial expressions and various lines and shapes that represent motion and cosmic energy. It is weird, technicolor, psychedelic stuff and I can’t believe little kids with slingshots in their back pockets and a dog with a spot over his eye or whatever were sitting around looking at this on the playground or hidden inside a math book.

Anyway Indiana Jones voice it belongs in a museum and you can get an original copy of #49 on ebay for just $9,000.

Listening

Every night I take a walk through my neighborhood. As much as I enjoy the afternoon howdy neighbor stroll with the dogs, after dark it’s a calmer experience and I can walk around maskless for the most part and not feel like an asshole, avoiding seeing more than a couple of people from a distance. I like to check out the exteriors of houses, and the different ways people are communicating their values and states of mind through them.

Mostly BLM, local election signs, thank you frontline workers signs, American flags. For a while there were a lot of chalk messages kids would leave for their friends. Every now and then you see a yard display that is unintentionally funny and/or horrifying. Like earlier in the week, I noticed this scene outside a fancy house (where I live it is like half-fancy, half-not so fancy you can guess which one we are).

On the left is a fairly innocuous laundry list of liberal values seen often in the neighborhoods of Boston. But just to the right is a sign advertising to passersby that this house is protected by SimpliSafe, a local security company owned by a notorious Trump supporter who treats his staff like shit. So yes of course we believe black lives matter but there is also a camera watching you right now so please stay the fuck off my property or an underpaid person in a call center somewhere will alert the police.

Anyway just wanted to share that cranky little tidbit before wrapping up. I also saw this week outside of a new fourplex an aggressive series of no fewer than five large flags, including your vanilla American flag, the fascist-adjacent “blue line” American flag, an Irish flag, and a Canadian flag. So just a friendly way to let the new neighbors know that you are white and perhaps have a certain amount of, what’s the word, pride about it.

Quite a time to be alive my friends. You know what? If it were logistically possible and my landlord would allow it, I would put flags up outside my house, one for each of you, with your beautiful faces on them. This is the better world I dream of.

Tate