46: Inalienable

A conversation with Cadwell Turnbull, author of The Lesson, about science fiction, colonialism, and redefining utopia

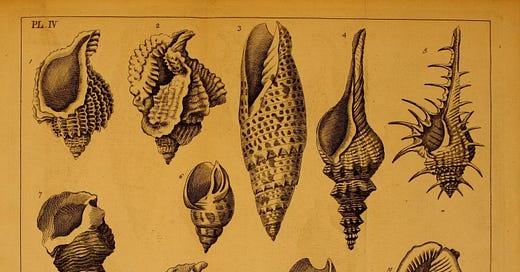

Elements of conchology, or, An introduction to the knowledge of shells. 1776.

The Lesson, the debut novel by Cadwell Turnbull, is one of best sci-fi novels I’ve read in years. It’s nominally an alien invasion story, but of a very different sort. For one, it takes place five years after the alien invasion, and it’s deeply character driven, opting to focus on how ordinary people’s lives are changed by the presence of powerful aliens, the Ynaa, who seem benign most of the time, but occasionally commit acts of brutal violence. The book is also a cutting exploration of colonialism, set in the past and present day U.S. Virgin Islands, where the author grew up. The Lesson received rave reviews and well-earned comparisons to the work of Octavia E. Butler and Ursula K. Le Guin.

Turnbull also recently wrote this insightful essay for Wired, “Dystopia Isn’t Sci-Fi—for Me, It’s the American Reality,” which I talked about in last week’s issue. That essay is what prompted me to reach out to him, as it explores a lot of themes of this newsletter, but I was also eager to talk about his fiction and his activism. He’s involved in Grassroots Economic Organizing, a collective that promotes worker co-ops and the solidarity economy—an economic model based on democratic participation, cooperation, and community ownership.

I really enjoyed our conversation, which is below in an abridged form, and lightly edited for clarity. You can also read the full interview here.

Be sure to check out The Lesson, available in all formats, and Turnbull’s other fiction. He’s contributed stories to The Dystopia Triptych, a series of just-released dystopian fiction anthologies, and Entanglements, an upcoming anthology from MIT Press edited by Sheila Williams. We spoke as he was preparing to relocate for a new job teaching at North Carolina State University, in the same program where he got his MFA. And the forthcoming first book in his new fantasy trilogy is titled No Gods No Monsters. OK here’s the interview.

One thing that I really loved about The Lesson is how vividly character driven it was. It's a very intense book, but there's also this kind of everyday drama about it that feels very real to me. There's this huge precariousness going on in the background, but then day-to-day life just kind of like marches on. And I wonder to what extent life feels that way to you.

In some ways, I wrote the book to have a conversation about colonialism and power dynamics, when someone is vastly more powerful than a particular group in a particular place, and they kind of lord over them up close and from afar, and that kind of relationship dynamic and what that does. And so now, even looking at all the stuff that's happening in America and across the world, there's that weird mix of normal life, and all of these politics that kind of feel distant, but they reach into your life.

And I would say that it's very similar, thinking about the Virgin Islands. Day to day, the Virgin Islands feels like it's all about these three islands and the people on them. But there's all these ways that being a part of the United States kind of tangentially plays into the culture and affects how we think about ourselves in relation to our place—how we think about people coming in, tourists, how we think about our various family members abroad. It's this way that we're always, even though it's very distant, relating ourselves to the mainland, to stateside.

And sometimes it's not that obvious, but our economy's very tourist heavy. So the cruise ships come in every week and people come off the cruise ships and they're all walking down Main Street and they're shopping and they're interacting with the commerce of the place, but not necessarily the people of the place. There's this interesting wall between those things, between normal life as a St. Thomian, and the tourist culture, people who are relating to us from a strictly commercial sense.

Yeah, it kind of reminds me of China Mieville's The City & the City. Where there's two cities that are superimposed on each other but they don’t interact. They're existing in the same space, but there's a disconnect.

Right. So like with the Ynaa, they interact with the island, kind of. Sometimes a member of the Ynaa will be walking down the street or they'll be eating some food. They're definitely a part of the island and the islanders know they're a part of it. And even though you could see the spaceship on the waterfront, the regular day-to-day stuff still feels the same, despite the fact that every once in a while you might pass an alien.

Right, right. Life just sort of goes on even though there's this tremendous threat that you could stumble across at any given time. I know you're a big Buffy fan, and I'm a big Buffy fan as well, and your work kind of reminds me of Buffy in the way it uses supernatural elements to bring out intensities of real life. It feels very real, even though there's this fantastical element. How much of that is intentional on your part? And what do you feel sci-fi and fantasy elements bring to your fiction?

I mean, in terms of Buffy, you know, I grew up watching that show. And it was always interesting to see these high schoolers fighting the forces of evil on the side, and occasionally a vampire showing up in the halls. But then on the regular day to day, the teachers didn't seem to be aware of it, like students would be absent because they were murdered off screen, right? And no one seemed to be like, hey where's Andy, he didn't show up to class today. I just always thought that was really fun and there seemed to be a playfulness to it. You know, at one point, the school actually just blows up. And Sunnydale proper just goes on as usual. And it seems like Sunnydale exists in some kind of weird snow globe where everyone else is like, yeah, that just happens there. But everywhere else, you know, we're normal over here.

And so yeah, engaging with that kind of media and enjoying it must have played a role in the way that I think about my fiction. I don't know if it was particularly conscious. I just know that when I was writing The Lesson, I didn't want to prioritize the aliens too much. I didn't want it to feel like it was about them. The human characters are relating to the Ynaa in different ways, but it's all very rooted in their own experience. And their relationship to other people, their relationship to the place, their questions about faith and sexuality, all these big things. For the people in the story, it seemed important to me that they relate to the Ynaa through themselves, not on the Ynaa's terms.

It's kind of like they're trying to not let the Ynaa's presence define who they are, but it's always this presence there in their lives.

Right. And I would say, it's similar to the Virgin Islands' relationship to the US. It is a presence. We are the US Virgin Islands, but when we talk about stateside, we say "stateside." We tend to separate ourselves, at least in a linguistic way, when we talk about the country we belong to. It's the country we belong to, but it’s not us all the time. It's kind of fluid.

You know, you mentioned you wanted to write a story about colonialism. And there's this common colonialism trope in especially classic science fiction. It's like terraforming other planets and setting up these outposts and conquering these distant monsters. I wonder how much of that bothered you being a science fiction fan, when you were growing up, or now. And how much, as you were writing your own alien story, you wanted to subvert those tropes in your work.

Yes, it bothered me. A lot of the time, I would engage with science fiction the way anybody would. I wasn't always being critical of it. One of my favorite shows was Stargate growing up, and I would watch Stargate and I didn't think about the militaristic aspect. It was fun. It was like, yeah, they were wearing military uniforms, but they were exploring other planets. And they had advisory roles on different planets, or they would mitigate some kind of disaster happening somewhere or some conflict between two nations on some planet. And I thought that was really interesting and fun.

I did not think about the fact that it was America doing that and how it fit into ideas about American imperialism, how how even on a galactic scale, America was centering itself and its concerns, and the story was bending over backwards to present this American worldview as being just and good. And, you know, we're saving the galaxy now, not just the world.

But there would be times when I was watching the show, and the team would be interacting with some locals or they would be mitigating some conflict, and I would find myself on the other side, defending the worldview of the people there or being like, you're not giving enough time to what they're feeling about your invasion, right? And I feel like at least it was stewing somewhere in my subconscious when I was young.

I think that that's truer to what would actually happen, that not everybody's relationship with the aliens would be equal on Earth. We're not just one human race. There are complicated power dynamics among us and those things would play out even in the midst of an alien presence.

As I got older, and I read more speculative fiction, I got more critical of the kinds of things I saw. I was like, why are the aliens always showing up to New York? Or DC? And why would they think those places are important? Why would it be important to them? When we explore other planets, why do we assume our supremacy in those contexts? Why don't we think that it's problematic to land on a planet without talking to the inhabitants first, and that kind of thing. But it took me a while to get there.

I feel like The Lesson, through writing it, I was also engaging with my critique of science fiction that I saw before and trying to do something different. And I didn't always know what I was critiquing or what was bothering me when I started.

One of the things that I refer to in the book is how the rest of the world treats the Virgin Islands, while the Virgin Islands is bearing the brunt of the Ynaa's existence. They're there, and they're causing legitimate harm to the community, but the rest of the world is benefiting from Ynaa technology. And there's a kind of saltiness the Virgin Islanders have in relation to the rest of the world because of that. I think that that's truer to what would actually happen, that not everybody's relationship with the aliens would be equal on Earth. We're not just one human race. There are complicated power dynamics among us and those things would play out even in the midst of an alien presence.

Well, in a way, you're talking about the presence of politics in your writing. I heard you say in another interview that a lot of times writers want to focus only on the personal. But that you can't separate the political from the personal because your politics are how you relate to the world. Can you elaborate on that?

I'll use healthcare for an example. I grew up in a cultural context where we were really hesitant to go to the doctor. There was a lot of anxiety attached to it. And I know that a lot of people have anxiety attached to going to the doctor. But within a community that is poor and doesn't have adequate health care and knows that going to the doctor is going to affect their ability to pay rent next week or feed their kids, there's a lot of extra anxiety about doing those kind of things. And so, those things are likely to be put off, and sometimes with disastrous consequences. I've had family members die because they didn't go to the hospital. Something was wrong with them, and they just didn’t know because they never went.

There's a reason why some people's homes feel more secure. And a lot of that has to do with systems. It has to do with how much pressure is on an individual, how much pressure is on a family, and those things have to do with larger political systems, not just what's happening in that one place.

So to me, you could write that story as a personal story about someone with a phobia of going to the hospital, and treat it as if it's just an individual thing. Or you could talk about the fact that most people don't have adequate health care, it's really expensive, it destabilizes people's households when someone gets sick. And so there's a lot of anxiety and fear attached to wellness, or seeking help, for physical health or mental health. And that is political. That is politics. That is policy.

You know, growing up, part of my family was on food stamps assistance and some of my aunts and cousins lived in public housing. Those things are attached to politics. There's a reason why some people are able to buy homes and create generational wealth, and some people can't. There's a reason why some people can afford to buy food on a regular basis, and some people have to struggle to buy food. That affects their health and that affects their levels of stress. There's a reason why some people's homes feel more secure. And a lot of that has to do with systems. It has to do with how much pressure is on an individual, how much pressure is on a family, and those things have to do with larger political systems, not just what's happening in that one place.

It's definitely a privilege to be able to not engage with politics. And not everybody has that ability to sort of separate it off as something that you might watch on TV or something on the news.

Right, it's happening to them.

Well, I guess that leads well into your essay for Wired, about dystopia and utopia. And I wanted to ask you about a couple things in that piece. So one topic that I thought was really powerful was the way you define utopia as being a move toward justice and equity, and not necessarily a perfect world. I wonder if you could kind of elaborate on, in your mind, what the difference is between justice and perfection.

We don't really have a good word for a just and equitable society. The way that I usually hear the conversation around utopia, and it kind of bugs me, is we use utopia as a stand in, both for our ideas of what a perfect society might look like, and what a just and equitable society might look like. And the conflation means that you can use the perfect society definition to gaslight the justice and equity one.

You can say, "perfection is impossible" to a question about housing, about education. It’s a way that we normalize the present and we pretend like the things that are happening—the injustices that we see in our current world—aren't the result of choices we're actually making. We can say, “Well, this is just the world. The world is not fair. The world is imperfect.” When what we're really talking about is that our systems are really bad. And that's a different conversation. But we don't treat them as different conversations.

Someone will say, we should make our society work for everyone, and someone else will say, what you're describing is utopia and utopia is impossible. This is good enough. We should improve upon this thing. When, in reality, this thing is really bad. And we should question the whole assumption of this thing.

I always think of how part of the American perspective is that some people deserve to thrive and some people don't, and it's not our jobs to say who does and who doesn't, we'll just sort of let it work itself out. And, you know, it's just natural that some people are going to suffer. I wonder if that's something that you think can change in the American perspective. It feels like such a big part of what the country is, I don't know.

I don't know, either. I mean, part of the reason why I was writing that essay was that I was grappling internally with a lot of things that I was feeling and that was the first time articulating what I felt was a huge problem. There's just a way that we operate that assumes a lot of things, and those assumptions, I think, are really bad and they perpetuate injustice.

There's a way that we just take for granted the suffering of marginalized groups of people. And that to get to a better society, those same people have to suffer more. Like arguing and arguing, being attacked, being discriminated against, in order to get people to recognize just their basic humanity. I feel like if we were to change the framing, at least in our conversations, we might get a step towards changing culture a little bit.

A meritocracy might determine whether you get a certain job or a certain paycheck, or whatever. I'm fine with that, but I just feel like people should be able to eat. That should not be an argument about merit. You know, no one should have to prove that they are deserving of eating.

The idea that some people should suffer is something we should challenge. And even if it's true that some people might end up suffering anyway, because suffering is a part of life, we should question it in terms of the operations of our systems. We should say, at the very least, everyone should be comfortable. And that should be something that we try to make true. And believe that it can exist. You know, health concerns are unavoidable, natural disasters are unavoidable, those kinds of things. But the system shouldn't be harming people, or killing people. And the system itself shouldn't be standing idly by as people suffer and die. That, to me, seems basic.

Part of this is a conversation around meritocracy. There should be a basic assumption of humanity and that should not be in question. A meritocracy might determine whether you get a certain job or a certain paycheck, or whatever. I'm fine with that, but I just feel like people should be able to eat. That should not be an argument about merit. You know, no one should have to prove that they are deserving of eating.

Yeah, I mean, there's a talking point among conservatives that not everybody deserves health care. That not everybody deserves to live and be healthy, which is such a strange sort of way to think about the world.

Yeah, like why? If you take a step back, it sounds absurd. If you were to remove all of the history of where that political opinion comes from and the way that we've normalized it. If you step back and just look at it, it seems ridiculous. It's like, no, everybody should have health care. Everybody should be able to eat, everybody should have shelter, all of the things that we know that people need to live and survive, everyone should have. There are real consequences when we don't think about what is inalienable for a human being, what a human being should just have.

Yeah, well, it reminds me of that line in your essay, which is, there is an assumption that injustice is normal, and that oppression is realistic. I wonder if you could talk a little bit about failure of imagination as a problem of injustice, and how we might get people to change what they believe is possible, or if that can be done.

On the second part of that question, I think that art is one way. I think about the reason I got into science fiction and genre, because I wanted to imagine alternatives to being and treat them as if those could be normal. So one of my favorite books is The Dispossessed by Ursula Le Guin. That story takes for granted that it's possible to have a political system based on everyone having what everybody else else has. And that there's some level of self governance that can be assumed, and that humanity wouldn't implode because of it. Life on Anarres is really hard, but everyone is relatively fine, and sharing resources isn't going to lead to the breakdown of society. That, to me, is really powerful. And you can't get there without creating a story around something like that, as if it's real.

You can't take reality for granted. The way that we've set things up was made by either deliberate or unconscious decisions, and the way that we change that is by deliberate or unconscious decisions.

But I think that in terms of activism, asking a question or critiquing a thing helps to challenge the assumption of its rightness and true-ness and centered-ness. If I ask a question like, why prison? Someone has to respond with, well, these are the reasons why we must have prisons, and then you can then have a conversation about each one of those things. Well, does our prison system do that? No, not really. Is it rehabilitating? No. Should we punish people in that way? Do you think that's a good way to punish people? Maybe not.

It's a way of renegotiating what we should consider normal. And to me that only works with engagement or asking the questions of why. You can't take reality for granted. The way that we've set things up was made by either deliberate or unconscious decisions, and the way that we change that is by deliberate or unconscious decisions.

Do you see your writing as part of your activism or your politics? Do you find them to be kind of the same thing? Or are they sort of different projects for you?

I think they're different projects. Ursula Le Guin talked about this, where she felt like her dedication was to her work. Her writing, that was her activism. And James Baldwin talks about this too, how he would try to join different organizations and then he would want to question them. And there's a way that even progressive or radical organizations assume certain things to be true and they don't challenge themselves on those assumptions.

With art, you can critique anything on a foundational level. Even the thing that you are presenting as a remedy. It teaches an underlying way of questioning, even when you think you're right, that I think is important and valuable to activism. It's important and valuable to social change.

I feel like, for my own brain, I really like fiction, because you can create a premise and you can also challenge a premise within it, and you need to. Inherent within fiction, you need to talk about conflict, or else it's not interesting, it's not a story. So reading The Dispossessed, that society is, I would say, much better than ours in terms of its ethics. But there are conflicts and problems within it. And those conflicts need to be resolved by the characters within the story.

There's a way that—and I don't want to say it like this—but there's a way when you are organizing with other people, you kind of have to drink the Kool Aid. You kind of have to like, critique it, but not critique it on a foundational level. Where I think that with art, you can critique anything on a foundational level. Even the thing that you are presenting as a remedy. It teaches an underlying way of questioning, even when you think you're right, that I think is important and valuable to activism. It's important and valuable to social change. And I just find stories where that is happening more compelling because I feel like the work is never done and your story should treat it that way, and you shouldn't assume that you've arrived at the answer. It's a step.

I wanted to ask you about your work with Grassroots Economic Organizing. I wonder if you could tell me about how you got involved with that group and what speaks to you about their work?

It came out of fiction. I'll tell you exactly what I was thinking about. I was thinking about having family that grew up in public housing, having grown up part of my life in public housing. I was thinking about how tight knit those communities are. You can really like walk next door and ask for sugar. It's not a cliche, it's a thing that you can do. One time, someone in our neighborhood bought bikes for a bunch of the kids on our street. Now, as an adult, I'm like, where did he get the money to buy those bikes? But at the time, it was really sweet and no one seemed to think it was odd. Everyone just got a bike and they were excited.

There was just that kind of relationship where you just knew everyone. You would go outside, and you'd walk down the sidewalk and pass the same people you pass every day, and they would ask you about your aunt and ask you about your cousin, ask about your mom or your grandmother. You'd be like, she's fine, how's so and so.

I was trying to imagine a speculative story where that same kind of culture was used to the economic benefit of the entire block or the entire community. They would create a business together, or cook food and deliver it to other people. Or they would buy cars together, they would create some kind of structure where they could buy a car and you could all use the car to do deliveries or whatever. All of these very working-class jobs, but they would pool that money into making the community stronger, investing in other things and other projects and other businesses. And that over time, they could create stability as a group.

I was like, what would that look like? And then I looked online, thinking, there must be something like this. And I found co-ops. I didn't know what a co-op was, and growing up, I couldn't point to one. We didn’t really have things set up that way. I feel like talking to people in the states, they at least know what a co-op grocery store is. But I had no conception of that. So I saw that, and over time, I got really interested in co-ops and started reading a lot more about them.

Through that work, which was at that time, research for a project that just never happened, I got submerged in the community. And then I met someone that was a part of a co-op, and they recommended Grassroots Economic Organizing to me. I thought what they were doing was really interesting. And then I joined.

But it came out of me trying to write a short story or something with this imagined cooperative structure. It turns out that it actually exists in the world. And there's a lot of different kinds of co-ops—housing co-ops, worker co-ops, co-op associations, open value networks, all of these interesting, cooperative setups. And most people don't really know about them. I was like, this is something that I could do, I could figure out a way to work with GEO to make these things better known or write about them, to engage with them in fiction.

I can see why that would be so appealing. I like the way co-ops chop up different parts of the existing economy and sort of piece together something totally new out of it, does that make sense?

Yeah, yeah, it does. Right now I've been working on a co-op game, like me and a few co-op people. We imagine a fictional co-op, and we've created characters within it, and we play them and they interact and they have conflict and there’s this larger world conflict that's happening. It's very cool.

Like a role playing game?

Like a role playing game. We Zoom. Well, we don't Zoom, there's this co-op version of Zoom. But we have these chats on Sundays, they last an hour and a half, two hours. And we have these shared characters and this shared co-op, and a shared world. We've been doing that for a number of weeks. And it's getting quite elaborate now.

Do you find that is a way to explore the possibilities of different concepts that could be put into place in co-ops, or is it just for fun?

It's both. A lot of us are just having fun with it. It's an opportunity for us to play on a new co-op model, and play out what the model would entail, but it's also really fun.

That's so cool. Okay, well, I want to get toward wrapping up here. I appreciate you taking the time to talk. I really enjoyed this, and I wish you the best in your writing and all these big life changes coming up.

Thank you. This was really great. I really enjoyed our conversation.

OK there’s the interview. And remember, the unabridged version is here, including lots of other great details about Cadwell’s writing process and more.

Podcasts

Back to the poetry corner this week, via Tracy K. Smith’s The Slowdown.

(First Trimester), by Craig Santos Perez

“they say plastic is the perfect creation

because it never dies…”

Watching

I am currently watching season 2 of The Strain. I was going to stop but now I’ve watched almost the whole season so I guess it’s got something going for it. It’s pretty gross, lots of worms crawling into eyeballs etc.

Jamie and I also watched Portrait of a Lady on Fire. While we were watching it, we were both honestly finding it a little slow to get going, real slow burn, slow and low. But it is an extremely beautiful movie and one that I was thinking about a lot after it was over, which I always think is one measure of a good movie.

Listening

I can do two in one newsletter it’s my newsletter. This video. 😮

Well next week we are going to try that age old coping strategy of running away from our problems. Specifically, driving to Western Massachusetts to stay in a cabin for 10 days, as we are doing next week because we must leave this house. That means, I’m sorry to inform you, that I’ll be skipping a week, maybe two weeks depending on how things go. Maybe I’ll send a best of or something.

Either way, you know I love you all as though you were my children that I do nothing to care for. So take care of yourselves. Take a deep breath. Maybe put a cold washcloth on your forehead for a couple of minutes. I’ll be back before you know it.

Tate