There is much to be said about Wednesday, not the least of which involves what we should even call it. An insurrection, a coup, an attack, a violent mob, a failed assassination attempt, this last one surfacing with new photos of nooses and bundles of zipties in the crowd. White supremacy and toxic masculinity in the flesh, four years of smashing, looting, pissing and shitting on the floor of government made literal by these grinning men with wild eyes, high on the knowledge that there are no real consequences for people like them. That all sounds accurately descriptive in its own way, but also incomplete.

Wednesday was one of those moments like 9/11 or the early days of COVID that offer such an acute distillation of What America Is, such a dizzying flash of truth that even if it’s a truth you already basically acknowledge, if you look at it right in the eyes or the buffalo horns as the case may be, you’re going to eventually throw up and then your brain is going to explode.

Maybe we can try to understand Wednesday by what it was not. It was not the conservative version of Black Lives Matter demonstrations—not equatable in scale or strategy, much less intent, one an authoritarian display of violence stoked by disinformation, the other a mass revolt against authoritarian violence. It was not merely internet trolls. I’m also wary of deploying the term terrorism, not because it’s too harsh, but because, as Farhad Ebrahimi pointed out, that is a dangerous word, and as Luke O’Neil wrote, such violence is always used as an excuse to expand the police state under the banner of anti-terrorism.

It was also not a historic aberration or a mere fringe element. It’s been said often, but I think it’s important to consider the way in which this is the continuation of a history of white violence—protecting power and privilege in response to demands for basic human rights—and the way in which it is the consequence of an ecosystem of disinformation designed to protect that power. Because both factors suggest this kind of thing is only going to keep happening.

Part of me feels like these are pretty obvious things to say, but Democrats and Republicans alike quickly fell back on the narrative of “this is not us,” labeling this as part of the blemish of Trump and a relatively small number of his supporters and we need to push it aside and move on. Another way to cast this misinterpretation is that the country is tragically divided between two equal and opposite political viewpoints, and that Trump just pushed the fringe of one side over the edge.

This ignores the fact that the attack, which happened the very morning after the pastor of Martin Luther King Jr.’s church was elected as the first Black senator from Georgia, is part of a long record of white violence in America—extrajudicial but often allowed or encouraged by authorities—in response to the expansion or defense of rights for non-white people. As Adam Serwer wrote yesterday, it was an attack on multiracial democracy, a “young, fragile experiment” that only dates back to 1965. White Americans have used violence to resist multiracial democracy as long as the country has existed, and continue to do so. Serwer points to the only coup d’état to take place on American soil, in Wilmington, North Carolina in 1898, when a former confederate soldier led a mob that killed dozens, shattered a Black middle class community, and overthrew the city government at gunpoint. It’s just one resonant example plucked from centuries that span slavery, Jim Crow, 6,500 lynchings, the Klan, the Proud Boys, the Trail of Tears, Tulsa, Birmingham, Boston schools, and on and on and on.

Violent white backlash in this current wave is owned and operated by the Republican Party, but it is in no way unique to the GOP, nor is it intrinsically a part of it, although it has thrived within the party’s narratives of personal liberty and government overreach. It doesn’t reflect the hearts of all Americans all the time, but none of us can wash our hands of it.

The other misrepresentation of what happened Wednesday is that it was merely an extreme expression of common, legitimate political beliefs. As Marco Rubio put it, “Millions of Americans had doubts about the election but didn’t sign up for a riot.” The rising extremism of Trump’s followers is dangerous, but the millions of Americans who had doubts about the election and didn’t sign up for a riot are at least as much of a problem for this country as those who did, as they are living in a manufactured reality in which violent resistance becomes a natural outcome. That reality was corroborated by 147 Republican lawmakers who voted to overturn a legitimate election based on nothing, a thank you and a pat on the back for the mob that was smashing in the building’s windows just hours earlier.

Yesterday, I was reminded of post-2016 election research on the media ecosystem that led to Trump’s victory in which the authors found that, contrary to common belief, social media does not inherently lead to polarization or belief in false information, nor are the left and right evenly divided up into their own custom realities. They did find significant media polarization, but it was asymmetrical, with one pole consuming a broad mix of mainstream and left-leaning media. The other pole was far to the right, isolated, and hyperpartisan, “an internally coherent, relatively insulated knowledge community,” which researchers found was driven by extreme outlets like Breitbart that pulled other right-leaning media like Fox News into their orbit. And that orbit is full of shit.

So what you end up with is a significant chunk of the American population that believes that the true tragedy that occurred on Wednesday is—not that a nauseating pack of conspiracy theorists ransacked a government building—but that Democrats and immigrants and corrupt, majority non-white cities stole an election. While bullets were flying in the Capitol, our mild-mannered conservative family members were mourning on Facebook this sad day in which Democrats stole the United States from them.

As history professor Timothy Snyder wrote yesterday, “The claim that Trump won the election is a big lie. A big lie changes reality. To believe it, people must disbelieve their senses, distrust their fellow citizens, and live in a world of faith. A big lie demands conspiracy thinking, since all who doubt it are seen as traitors. A big lie undoes a society, since it divides citizens into believers and unbelievers. … A big lie must bring violence, as it has.”

There is, of course, a connection and a warning here about climate change. Another big lie—that climate change is not real—has been perpetrated for decades through a similar ecosystem of disinformation, as a way of similarly protecting power and wealth. And if this sounds like a reach, remember that for vulnerable communities and disproportionately for non-white people, climate justice is a fight for the right to exist. And for people who have not found climate change knocking at their door yet (keeping in mind nobody will escape it), the demands of those communities to exist are often viewed as a direct infringement on their own freedom and way of life. If there is any doubt of that, we only need remember the violence unleashed on the Standing Rock Sioux and other Native communities who defended their right to clean water as opposed to a new piece of fossil fuel infrastructure.

These parallels aren’t unique to the climate fight, but what we saw on Wednesday was not a blip or a culmination or a last gasp of Trumpism—it’s representative of a pervasive struggle in America for basic human rights across many interconnected issues, including climate and environmental justice. And when these struggles continue to come to a head in the future, and a large part of the population continues to be told relentlessly that something that rightfully belongs to them is being stolen, Wednesday will show its grinning, wild-eyed face, again and again.

Links

“Trump supporters across the country now believe that the nation has been stolen from them. Whether they rule by force, fraud, or law, their rule is the only acceptable outcome.”

Police are more than twice as likely to attempt to break up a left-wing protest than a right-wing one, and when they do intervene, they are more likely to use force.

These 147 Republicans voted to overturn a presidential election.

“White supremacy was on full display. The world saw it.”

“These guys were intent on inflicting suffering and punishment on other people — it’s the opposite of civil disobedience. And oddly, it was met with the opposite reaction.”

“Tomorrow, these hundreds of MAGA sycophants and the millions who support them will take off their stupid hats and Punisher cosplay attire and walk among us again.”

“It is America if you know any history deeper than the United States’ greatest hits. This coup deeply echoes the end of Reconstruction, the defining political realignment of our age that the vast majority of us knows nothing about.”

Capitol rioters planned for weeks in plain sight.

The U.S. Capitol police force has 2,300 officers to protect 16 acres of ground, almost three times the number of officers in the entire city of Minneapolis. “Was there a structural feeling that well, these are a bunch of conservatives, they’re not going to do anything like this? Quite possibly.”

AHP on how to work through a coup.

Emily Atkin’s fantastic defense of Sunrise Movement against dudes like Matt Yglesias who believe that climate reality is too politically radical.

“Let’s be honest: Crime coverage is terrible. It’s racist, classist, fear-based clickbait masking as journalism.”

Communication and cooperation between trees within a forest challenge ideas of cutthroat competition for resources in nature. (ht to my friend Pat who forwarded this one to me)

Listening

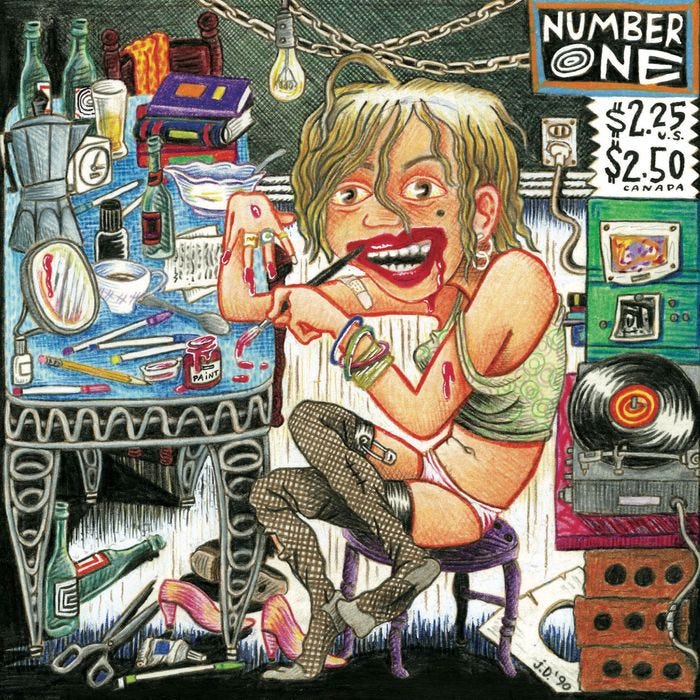

Comics

Dirty Plotte, The Complete Julie Doucet

Reading

“What we were completely missing, however, was the concept of death itself, death absolute. The kind of death that comes to us all, irrespective of position. Death absolute is the truth of our existence as a whole, of course, but America has rarely been philosophically inclined to consider existence as a whole, preferring instead to attack death as a series of discrete problems. Wars on drugs, cancer, poverty, and so on. …

Untimely death has rarely been random in these United States. It has usually had a precise physiognomy, location and bottom line. For millions of Americans, it’s always been a war.”

I know this is everyone’s favorite part when I tell a fun little story or a joke or something, but I’m out of steam. I do want to give some space here to celebrate the Senate race in Georgia, especially Raphael Warnock’s historic win. One of the many tragedies of this week is that the voter turnout and amazing work that organizers have been doing there was overwhelmed by the devastating news. I know this was a bleak issue, but our better natures really do win sometimes. We’re not doomed and we can learn and change. We can be angry and sad and hopeful at the same time. Lot of things true at once. Lot of emojis (which is my nickname for emotions) swirling around in there. Get some sleep.

Tate