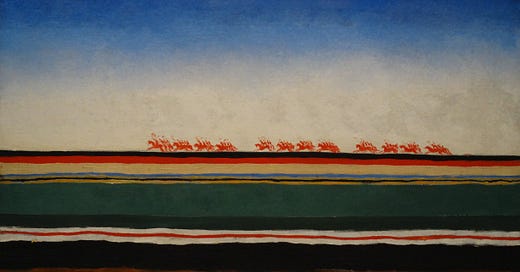

Red Cavalry, Kazimir Malevich, 1932

Earlier this year, two miles west of my house, a woman named Marilyn Wentworth was crossing the street to get a coffee at her favorite shop, a little family-owned place I go to all the time. As she used the crosswalk to navigate the four lanes of traffic that rip through the neighborhood’s business district, a car struck and killed her. Her husband of 42 years reported seeing her body “fly in the air.”

That’s a particularly dangerous stretch of road, even for Boston, and the city is now pursuing a plan that would remove one car lane and add protected bike lanes. The Wentworth family and many others are advocating for it. But as you can imagine, there’s a lot of resistance. At a recent public meeting on the plan, one city council candidate charged the mic and said, “This is not a good idea.”

That there’s any resistance at all is a testament to the dedication with which someone will defend their right to strap themselves into a two-ton cocoon of plastic and steel to get anywhere they want to go, as fast as they want to go, with as few impediments as possible.

That tragedy, others like it, having to drive around metro Boston, and the purchase of a new bike have all contributed to my own increasingly severe reassessment of the act of driving.

Growing up in the West, driving unambiguously meant freedom. Going 55 mph on sprawling suburban roads just to get a pizza or whatever. Vast stretches of open highway ultimately leading to the Pacific Ocean. Careening through the Mid-Atlantic to see fireflies for the first time. Criss-crossing the country in my 20s as many ways as I could, over and over.

These days, I’m more likely to think of driving as a menacing, harmful act, something I want to avoid as much as humanly possible. If you’re like whoa whoa pal sounds like you’re saying people who drive are bad people, keep in mind that I do drive a car. Jamie (Borat voice my wife) and I are fortunate enough to not have to drive very much where we live, but we still make a few car trips most weeks, plus occasional weekend trips out of the city.

But when I get behind the wheel, I know that I’m a much worse person than I am when I’m not driving. I’m angry. I’m impatient. I’m unforgiving toward those around me. In no other setting do I think or say worse things about other humans except possibly on twitter. Statistics tell me I’m more likely to die from a road injury than any cause other than disease, and it’s the only activity I do where there’s at least an outlying chance that I will kill someone. (Of course, there would probably be no punishment, as killing a pedestrian while driving has been described as “the perfect crime.”)

The mean streets of Roslindale.

If you’re thinking, boy sounds like you need to become a safer driver, the numbers betray the case for individual blame. Pedestrian deaths in the United States are at a 30-year high (6,227 in 2018). A Guardian article this week on the topic explored why that number has been climbing, and the reasons are complex. But experts have no shortage of explanations for why roads are so much more dangerous here than in any other wealthy country—we drive more, we drive farther across urban sprawl, we drive faster and faster, though we know speed increases likelihood of death. More Americans than ever drive SUVs and trucks, which are between two and three times more likely to kill the people they hit. Experts largely doubt that automation technology in cars will solve this problem. In short, cars rule our roads.

There does seem to be a growing intolerance of this fact of American life. Recently, Allison Arieff, a writer on design and cities, wrote a column for the New York Times in which she made the case that “Cars are Death Machines,” recounting several personal stories of death and injury by car from among the hundreds she collected on Twitter.

We all have these stories. You do. I certainly do, though I feel like I can’t do my own justice in newsletter form. Despite our losses and pain, we allow cars to remain dominant.

We usually talk about emissions and climate change as separate issues from car safety, but I don’t really see them as all that different. In both cases, it’s a matter of personal freedom and convenience, disproportionately distributed, at the cost of collective health and safety. Transportation is now the largest source of American greenhouse gas emissions. A recent report showed that for all its progress California is not on track to hit its own emissions reduction goals, in large part because of its passenger vehicles. Traffic deaths and climate change are both consequences of a particular way we choose to live. One way or another, you turn the key, harm is being done.

I imagine we’ll always have cars, and yes, more electric vehicles if powered by renewables will reduce emissions. And again, I’m not trying to castigate anyone who drives a car, we’re all doing the best we can out here my dudes. But the strides we need to make on fossil fuel use and our deadly roads both point to the reality that we’ve just got to stop driving so much. And stop designing the world around us to cater overwhelmingly to cars.

That’s an entirely possible future. Prior to the 1970s, the Netherlands was far more car friendly and dangerous, but public outcry forced the pedestrian and cyclist paradise into reality. Even here in the States, in the 1950s and 1960s, we once had a mass movement of mothers demanding safer streets, blocking car traffic with baby carriages in radical demonstrations. And in the Boston neighborhood where Marilyn Wentworth was killed, residents formed a new group to advocate for pedestrian rights. There’s one in my neighborhood too.

And in the meantime, I’m going to keep driving as little as I can. And when I do drive, I will drive very, very slowly. Sorry and you’re welcome.

Links

The next Standing Rock is everywhere.

David Roberts predictably did a much better job writing about the Climate Emergency Fund than that Times article I was mad about last week. I will still respectfully note that I wrote about the fund three months ago ahem.

Unfortunate trends, and the most detailed map of auto emissions in America.

Salt water is creeping toward inland trees, creating dead, bleached, and blackened “ghost forests.”

The Klamath River now has the rights of a person under tribal law.

“For the first time on record, the 400 wealthiest Americans last year paid a lower total tax rate than any other income group.”

Argentine feminists are reclaiming the tango to make it less patriarchal.

The rare Fiona Apple interview is always a real gem. She’s also working on a new album, AND Pitchfork named Idler Wheel… the #5 album of the 2010s. It’s all coming up Fiona.

Listening

Since it’s Fiona’s world I thought I would keep it going and highlight a song of hers that I’ve been listening to lately. This is actually both a cover and a collaboration between King Princess and Fiona Apple, recording the final song on 1999’s When the Pawn. It is a good song and a good version.

Here’s a fun thing, after When the Pawn came out, Fiona Apple toured behind it in 2000 and then after an onstage breakdown took a five-year hiatus from performing and had this whole fiasco with her record label trying to stop Extraordinary Machine from coming out.

Well, when that album was finally released, she played her very first show in five years at the Roseland Theater in Portland, Oregon in 2005, and you know what, I was there. She put on a beautiful show and crowd was so warm and encouraging so that’s a nice memory. Fiona forever.

Watching

During October I watch scary movies pretty much exclusively and I always find it interesting how sometimes bad scary movies are the scariest and good scary movies aren’t really that scary. Goes to show you never really know what you’re going to be afraid of. It’s a real treat when a movie is both good and scary and so far this year, Lake Mungo scores high.

We are having what they call a mast year for acorns in New England which is a totally natural part of the boom and bust cycle of oak tree fruit, no climate change to see here move along. But it means there are acorns everywhere, lining the sidewalks, squirrels chucking them down on your head or the roof of your car like you’re some kind of Mister Magoo.

My sister just came to visit from Arizona and we saw some acorns and she said oh acorns my students love the ones I brought back last year we still have them. She works with tiny kids and for tiny kids in the desert, an acorn must be some kind of fairy tale object like a spindle or magic beans. Then later on I walked on a patch of like a hundred acorns and lost my balance for a second like a cartoon burglar walking on marbles.

So the lesson here is, if you see just a few acorns, pick one up and give it to a tiny child because they will be super into it. If you see many acorns in one place, be careful because you could fall and break your ass.

Tate